Women in STEM

Resource Page

Repository of peer-reviewed research

of the challenges facing women

in science.

Introduction

I once thought that due to the efforts of the past generation of women, the fight for equality was over. One day, sitting as a senior in Prof Jay Gamble’s class at the University of Calgary, I said as much when he was giving his arguments as to why feminism is important today and benefits men as well as women. I said, “At least women are paid the same today.” I’ll never forget when he looked at me and said, “Oh, you think you’ll get paid the same as a future physics professor? Check out the latest report on the earnings of female and male professors across the universities in Canada.” This sentence changed my life and I started to check out the continuing bias facing women in science and in the workforce in general. I looked it up and even for the same field of study, same rank, and same hours worked there existed a small but persistent pay gap.

To be clear - women have made massive progress. I would much rather be a woman today in physics than in 1960s. This page is dedicated to exploring where demonstratable gender or racial bias still exists when comparing the same job and the same hours, rather than comparing all women to all men. Below is a repository of peer-reviewed research of bias still facing women and minorities in science.

Personal Experiences

I was lucky that my dad was a physicist, and I never thought I couldn't be one due to his supportive role model. But I have heard somethings which I wish I hadn't.

Once while in a job interview for a faculty position, I was asked if I was married, and if I wanted to have kids. I was asked if my husband would move with me for the job, and when I said yes, the response was "Oh! That's unusual, usually the wife follows the man." At the same interview, the external member of the committee missed the two male candidates research talks and the reason given was "he already knows the men's research, he doesn't know the women's research." In the room where we gave our research talk there was a poster saying "Don't ask me about my skirt, ask me about my science." But that was not the sort of sexism that was happening. And sadly it was completely invisible to the department.

I saw a presentation once where the male students for this professor's group were literally in larger font. And he only described them as "brilliant." The change in font size was particularly cartoonish.

Another story that stands out was when my PhD advisor was directly undercut by comments. I overheard several myself, but one that was really egregious was when another male professor in the department told his student to directly ignore her advice on the committee because "she is a woman" and "women are less aggressive and ambitious" and that "we will do the male thing and pursue the higher risk project which might yeild no papers during the PhD". I honestly don't know if that student is still in academia or not, but the framing of her advice was alarming. Even if you disagree with your colleague's advice on rational grounds, which I am highly suspect here, reaching for a gender stereotype and propagating that to the next generation is wrong.

These stereotypes are of course, not limited to academia. A friend told me directly that women can't be good engineers - we cry to much. This was while we were at high altitude, and the 50% oxygen around 19,000 ft. meant that a lot of unfiltered thoughts and misogeny came out. It's a fairly well known phenomenon in high altitude moutnaineering circles and the medical literature. A family member told me that she wouldn't want to have a female pilot. Interestingly enough her husband is a pilot and said in that moment that women have a better safety record and faster reaction times. But she held her opinion, saying "I just wouldn't be comfortable." Everyone has a miriad of stories, but these are a few.

Peer-reviewed research about women in STEM

Discounting Counter-Stereotypical Representations in Entertainment Based on Existing Beliefs. Mustafaj & Dal Cin (2024).

Brilliant characters often play key roles in movies and TV shows. However, when these characters are played by women and people of color, some audience members dismiss them as unrealistic, even if they portray real people and events, a recent study found.

Citation: Mustafaj, M., & Dal Cin, S. (2024). Media Psychology, 1-12

I forgot that you existed: Role of memory accessibility in the gender citation gap, Yan et al. (2024)

Women receive 30% less citations than men in psychology. This is especially unexpected since women make up 2/3rds of faculty. One possible explanation is that women's work is less good but there is no evidence of that. The authors propose that it could be that male professors' more easily remember their male colleagues' work. When asked to recall five experts in the field, male researchers listed more men and also put the men first on the list. Women recalled equally and they did not vary the order in which they listed men and women.

Citation: Yan et al. (2024) American Psychologist.

Professors’ Biased Evaluations of Physics and Biology Post-Doctoral Candidates (Eaton et al. 2020)

This study is fascintating as it shows yet again, another identical CV but different name study of evalucating postdoctoral applications of candidates with male/female names and Asian/White/Black/Latinx names. White and Asian candidates were ranked higher than Black and Latinx candidates, and men were ranked more competent than women, though women were deemed more likeable. Naturally, Black and Latina women face the greatest bias. This study was run at 8 large public universities in the US in physics and biology departments. The names were: Bradley Miller (white male), Claire Miller (white female), Zhang Wei [David] (Asian male), Wang Li [Lily] (Asian female), Jamal Banks (Black male), Shanice Banks (Black female), José Rodriguez (Latino male), and Maria Rodriguez (the Latina female). However, it is critical to note that only physics faculty, not biology faculty, exhibited a general gender bias in their evaluations of the candidates’ competence and hireability.

Citation: Eaton et al. (2020) Sex Roles, 82, 127–141.

Women are better at statistics than they think (MacArthur 2022)

Women do better in statistic classes than men despite thinking they don't have the skills and having more negative attitudes about their abilities.

Here is a write up from the authors about their study in lay terms.

Citation: MacArthur & Santo (2022) Journal of Statistics and Data Science Education

The rise of citational justice: how scholars are making references fairer (Kwon 2022)

Women, particularly women of color are not cited as often as white women or white men researchers. Just as "like hires like" we see the same implicit bias in citations. People cite those who look like themselves, who are from the same geographical location or institutions, and who are known to them. This means that women and especially women of color and researchers in the global South are not cited at the same rate for the same quality of research as their peers. Christen Smith started the Cite Black Women movement after seeing her work at conferences being uncited and that movement has now grown and has a podcast, website, and blog, highlighting this issue.

Citation: Kwon (2022) Nature

Understanding persistent gender gaps in STEM (Cimpian et al. 2020)

While the overall STEM gap has decreased substantially, such that undergraduate majors are now 1-1 for men and women in chemistry, biology, and mathematics, in physics, engineering and computer science (PECS) the gap has stubbornly stalled at 4-1. What is more unusual, is that when looking at the bottom vs top ranking students, more lower ranking male students stay in PECS fields compared to female students.

Citation: Cimpian et al. (2020) Science, 368:6497, 1317-1319.

When women enter a field, pay drops (Levanon et al. 2009)

Jobs with the similar skill, education, and responsibility, women's pay is significantly lower compared to men. Furthermore, when women enter a field in large numbers, the pay for the whole field drops even after controlling for education, work experience, skills, race and geography. Park and recreation workers used to be male dominated in the 1950s, but by the 2000s when the field was predominately women, pay dropped 57%. Significant drops were seen when other professions switched from male to female dominated, such as ticket agents (pay dropped 43%), designers (34%), housekeepers (21%), biologists (18%). Woman doctors earn 72% of men, women laywers earn 82%. Janitors are paid more than maids, though the work is similar. Computer programming used to be low paid and was predominately done by women, but then it became male dominated and the wage increased. To fix the pay gap, we need to value work done by all genders equally. New York Times articlesummarizing the peer reviewed article.

Citation: Levanon et al. (2009), Occupational Feminization and Pay: Assessing Causal Dynamics Using 1950-2000 U.S. Census Data, Social Forces 88(2) 865–892.

Science faculty’s subtle gender biases favor male students (Moss-Racusin et al., 2012)

The study used a clever design, in which an application, modified to be either from "Jennifer" or "John" was given to a male or female faculty member for evaluation. Evaluators in biology, chemistry and physics departments at six highly ranked research universities were told the résumé was real and that the evaluation would be used to develop mentoring materials for science students.

There were two key findings: First, "Jennifer" received significantly lower ratings than ‘John,’ and second, male and female evaluators were equally likely to give "Jennifer" lower ratings. The ratings pertained to competence, hireability and whether the candidate was deserving of mentoring. The evaluators made lower salary recommendations (by about 12 percent) for "Jennifer" relative to "John."

Note: Biology professors, for example, whose classes can be >50% female, were just as biased as physicists. Women professors were just as biased as men. Junior professors were just as biased as seniors.

Press release summary of study

Citation: Moss-Racusin et al. (2012) PNAS, 109 (41) 16474.

Students are significantly biased toward female lecturers (Mengel et al.,2017)

Evaluations place female lecturers, particularly junior ones, 37 slots below male ones. This is largely driven by male student evaluations and more pronounced in mathematical courses though female students also rated female lecturers lower. In the study, the students had the same course materials, on average had the same grades, and the same contact hours etc. Another, sad and distrubing, study showed the same effect when the true gender of the professor was unknown in an online course, but evaluations were higher for the instructors that were given a male identity (MacNell et al., 2015). The study invovled German, Asian, Dutch and European students.

This is especially important to consider for promotions since women will appear "objectively" less qualified than an equally male lecturer and may influence tenure rates.

Press release summary of study in the Economist

Citation: Mengal et al. (2017) IZA Institute of Labor Economics Discussion Paper No. 11000

Salaries for female physics faculty trail those for male colleagues

"In physics men earn, on average, 18% more than women, according to a survey by the Statistical Research Center (SRC) at the American Institute of Physics (which publishes this magazine). The survey looked at people who received their physics PhDs in the US in 1996, 1997, 2000, or 2001 and who were working in the country in 2011. After accounting for other factors, such as employment sector, postdoctoral experience, and age, a 5.7% disparity persists. That difference is attributable to sex, says the SRC’s Susan White, who analyzed the data. 'The model says that if we have two people who are identical in every way, the woman will make, on average, 6% less than the man.' "

summarized by Toni FederCitation: Physics Today 70, 11, 24 (2017);

View online: https://doi.org/10.1063/PT.3.3760

Even small differences in salary (1-3%) accumulate to large amounts (Rao, et al., 2018)

Even a small pay difference between 1-3% can lead to lifetime losses of up to a half million dollars. We need to retroactively increase pay. Findings summarized in Science daily: "The researchers then calculated lifetime wealth accumulation under three different scenarios. A woman hired in 2005, they showed, would have accumulated $501,416 less in eventual salary and investment returns than a man hired at the same time if gender equity initiatives had not narrowed the pay gap from 2.6 to 1.9 percent. In a more real-time, fluid scenario, a woman hired in 2005 whose pay and promotions were positively affected by the initiative from 2006 through 2016 would go on to accumulate $210,829 less than a man in that position. And finally, a woman hired in 2016, with the 1.9 percent pay gap, is projected to accumulate $66,104 less."

Citation: Rao, A.D. et al., (2018) Association of a Simulated Institutional Gender Equity Initiative With Gender-Based Disparities in Medical School Faculty Salaries and Promotions. JAMA Network Open 1 (8): e186054 DOI: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2018.6054

Press release: https://www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2019/01/190128111728.htm

Letters of recommendation are shorter and less positive for female postdocs (Dutt et al. 2016)

"Our results reveal that female applicants are only half as likely to receive excellent letters versus good letters compared to male applicants. We also find no evidence that male and female recommenders differ in their likelihood to write stronger letters for male applicants over female applicants. Our analysis also reveals significant regional differences in letter length, with letters from the Americas being significantly longer than any other region, whereas letter tone appears to be distributed equivalently across all world regions. These results suggest that women are significantly less likely to receive excellent recommendation letters than their male counterparts at a critical juncture in their career."

Citation: Dutt, K., et al. (2016) Gender differences in recommendation letters for postdoctoral fellowships in geoscience. Nature Geoscience volume 9, pages805–808 (2016)

Women of Color Face Greatest Bias in Science (Clancy, K. et al. 2017)

Not a surprising result, but horrifying nonetheless. 40% of women of color reported feeling unsafe in the workplace as a result of their gender or sex, and 28% of women of color reported feeling unsafe as a result of their race. Finally, 18% of women of color, and 12% of white women, skipped professional events because they did not feel safe attending, identifying a significant loss of career opportunities due to a hostile climate.

Citation: Clancy, K., et al. Double jeopardy in astronomy and planetary science: Women of color face greater risks of gendered and racial harassment. AGU, vol 122, issue 7 (2017) https://doi.org/10.1002/2017JE005256

Females show more sustained performance during test-taking than males (Balart and Oosterveen 2019)

Interestingly, the gender performance gap in math and science testing seems to go away if you provide more time. Women seem to have better test endurance and perhaps need the extra time to overcome stereotype threat or text anxiety which may otherwise have limited performance.

Press release in Newsweek

Citation: Balart and Oosterveen Nature Communications volume 10, Article number: 3798 (2019).

Males Under-Estimate Academic Performance of Their Female Peers in Undergraduate Biology Classrooms (Grunspan et al. 2016)

This study found that males enrolled in undergraduate biology classes consistently ranked their male classmates as more knowledgeable about course content, even over better-performing female students. Men ranked other men by 0.57 GPA points (on a 4 point scale) higher than equally performing female students. "Using UW’s standard grade scale, that’s like believing a male with a B and a female with an A have the same ability," said co-lead author Sarah Eddy. This was not true of female biology students who ranked equally male and female peers.

Press release

Grunspan, D., et al. (2016) Males Under-Estimate Academic Performance of Their Female Peers in Undergraduate Biology Classrooms. PLoS ONE 11(2): e0148405. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0148405

Quality of evidence revealing subtle gender biases in science is in the eye of the beholder (Handley et al. 2016)

This study shows that male academics are more likely to dismiss real studies showing gender bias as shoddy work while accepting the findings of fake research which show that there is no gender bias in STEM. Ironically this paper started a debate on my facebook wall with a male scientist pointing out the flaws in this study while unaware that he was proving the study correct in real time. It's a non-paradigm shattering demonstration that paradigms impact us all and we will use motivated reasoning, even as scientists, to confirm our perferred worldivew.

Press release summary of study from Wired: Why Men Don't Believe the Data on Gender Bias

Citation: Handley et al. (2016) PNAS, 112 (43) 13201–13206. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1510649112

Faculty respond to white men more than women or people of color. Milkman et al. 2015

This study shows that professors will respond to inquiries of potential doctoral students more frequently to white male names over white women or women and men of color. The inquiries were the exact same except for the name...

Citation: Milkman, Chugh & Akinola (2015) Journal of Applied Psychology, 100 (6): 1678-1712. DOI: 10.1037/apl0000022

Where are the Gender Differences? Male Priming Boosts Spatial Skills in Women (Ortner & Sieverding 2008)

Spatial reasoning is one of those gender differences that seemed to be genuine and related to known hormonal differences, including in men with varying testosterone levels. However, this study shows that if a woman imaging herself as a stereotypical male, then that gap in spatial reasoning disappears. A man spend time imaging himself in stereotypical female roles does not notice a decline from their baseline spatial reasoning. This only helps women and is neutral to men, and strongly indicates that spatial reasoning is not as gendered as previously thought. Stereotype threat is a powerful effect that needs to be addressed in our classrooms, job interviews, and in test environments. Nice blog overview of this and other studies related to stereotype threat and test performance from MIT admissions: Picture yourself as a stereotypical maleCitation: Ortner & Siverding (2008) Sex Roles, 59:274–281. DOI 10.1007/s11199-008-9448-9

Impact of Gender on the Cirricula Vitae of Job Applicants and Tenure Applicants: A National Empirical Study. (Steinpreis et al. 1999)

This is a similar research study as the Moss-Racuin study above except that it is at the professor level. The bias seems to be worse the higher up you go. In a national study, 238 academic psychologists (118 male, 120 female) evaluated a resume randomly assigned a male or a female name. Panels composed of male and female university psychology professors were asked to evaluate application packages for either "Brian" or "Karen" and determine the candidate’s suitability as an assistant professor. The panels preferred 2:1 to hire "Brian" over "Karen," even though the application packages were identical except for the name. When evaluating a more experienced record (at the point of promotion to tenure), the panel members expressed reservations four times more often for "Karen" than for "Brian." Both male and female participants gave the male applicant better evaluations for teaching, research, and service experience and both were more likely to hire the male than the female applicant.

Citation: Steinpreis, R., Anders, K.A., and Ritzke, D. (1999) "The impact of gender on the review of the curricula vitae of job applicants and tenure candidates: A national empirical study." Sex Roles 41: 509-528.

Mother penalty, Daddy Bonus (Correll et al. 2007)

Correll, Benard & Paik (2007) extended the study to mothers. Panels were asked to evaluate application packages that were identical except for one line in the CV: "Active in the PTA." Evaluators rated mothers as less competent and committed to paid work than non-mothers. Prospective employers called mothers back about half as often. Mothers were less likely to be recommended for hire, promotion, and management. Mothers were offered lower starting salaries. When a similar study was done for fathers, however, the results were quite different. Fathers were not disadvantaged in the hiring process. They were seen as more committed to paid work, and were offered higher starting salaries.

Citation: Correll, Benard & Paik (2007) American Journal of Sociology, 112 (5), 1297.

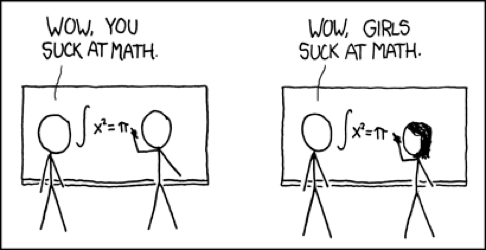

Gender stereotypes about intellectual ability emerge early and influence children’s interests (Bian et al. 2017)

The distribution of women and men across academic disciplines seems to be affected by perceptions of intellectual brilliance. Bian et al. studied young children to assess when those differential perceptions emerge. At age 5, children seemed not to differentiate between boys and girls in expectations of "really, really smart"—childhood's version of adult brilliance. But by age 6, girls were prepared to lump more boys into the “really, really smart” category and to steer themselves away from games intended for the "really, really smart."

Citation: Bian, L., Leslie, S., Cimpian, A. (2017) Science, 355, 6323, pp. 389-391

The Possible Role of Resource Requirements and Academic Career-Choice Risk on Gender Differences in Publication Rate and Impact (Duch et al., 2012)

From Abstract: We built a unique database that comprises 437,787 publications authored by 4,292 faculty members at top United States research universities. Our analyses reveal that gender differences in publication rate and impact are discipline-specific. Our results also support two hypotheses. First, the widely-reported lower publication rates of female faculty are correlated with the amount of research resources typically needed in the discipline considered, and thus may be explained by the lower level of institutional support historically received by females. Second, in disciplines where pursuing an academic position incurs greater career risk, female faculty tend to have a greater fraction of higher impact publications than males.

Press Release

Citation: Duch et al. 2012 The Possible Role of Resource Requirements and Academic Career-Choice Risk on Gender Differences in Publication Rate and Impact, PLoS ONE 7(12): e51332. DOI 10.1371/journal.pone.0051332

Full text article (open source)

Bias is greater when small pool of applicants (Heilman, 1980)

Another study showed that the preference for males was greater when women represented a small proportion of the pool of candidates, as is typical in many academic fields.

Citation: Heilman, M. E., “The impact of situational factors on personnel decisions concerning women: varying the sexcomposition of the applicant pool,” Organizational Behavior and Human Performance 26 (1980): 386-395.

Bias in letters of recommendation (Trix and Psenka, 2003).

A study of over 300 recommendation letters for medical faculty at a large American medical school in the 1990s found that letters for female applicants differed systematically from those for males. Letters written for women were shorter, provided “minimal assurance” rather than solid recommendation, raised more doubts, and portrayed women as students and teachers while portraying men as researchers and professionals. While such differences were readily apparent, it is important to note that all letters studied were for successful candidates only.

Trix, F. and Psenka, C., “Exploring the color of glass: Letters of recommendation for female and male medical faculty,” Discourse & Society 14(2003): 191-220.

Women ask fewer questions than men (Carter et al, 2018)

The main finding is that female audience members asked absolutely and proportionally fewer questions than male audience members at the ~250 academic seminars we observed around the world. They noticed that this imbalance was less pronounced when the first question was asked by a woman. They suggest that the results are best explained by internalized gender role stereotypes about assertiveness and propose recommendations for increasing women’s visibility at these events.

Carter, A., Croft, A., Lukas, D., Sandstrom, G., “Women's visibility in academic seminars: women ask fewer questions than men.” PLoS One (2018). arXiv Preprint

Women need much more publications to be considered equal (Wenneras and Wold, 1997)

A study of postdoctoral fellowships awarded by the Medical Research Council in Sweden, found that women candidates needed substantially more publications (the equivalent of 3 more papers in Nature or Science, or 20 more papers in specialty journals such as Infection and Immunity or Neuroscience) to achieve the same rating as men, unless they personally knew someone on the panel.

Wenneras, C. and Wold, A., “Nepotism and sexism in peer-review,” Nature. 387(1997): 341-43.

Stereotypes About Gender and Science: Women ≠ Scientists

This study by psychologist Linda Carli et al., shows that while men and scientists are associated with being independent and agentic (proactive, self-motivating), women are perceived as being communal and not having these desirable traits for scientists. This lack of fit may contribute to bias against women in STEM fields.

Citation: Carli, L. L., et al. (2016) Stereotypes About Gender and Science: Women ≠ Scientists. Psychology of Women Quarterly. Vol. 40(2) 244-260.Press Release

On the negatives of benevolent sexism (Becker and Wright, 2011)

Becker, J., and Wright, S. (2011). Yet another dark side of chivalry: Benevolent sexism undermines and hostile sexism motivates collective action for social change. Citation: Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 101 (1), 62-77 DOI: 10.1037/a0022615

Marital status hurts women and helps men

A 2010 survey by the American Historical Association showed some interesting trends in the promotion rates between men and women, particularly when marriage is included. Note some of these effects can be explained by accounting for the age (and thus larger historical inequities), but not all. More interesting is that married men fare better than single men whereas the opposite is true for married women in academia. Married or previously married female historians took an average of 7.8 years to move from associate to full professor. Women who had never married were promoted in an average of 6.7 years. Married men took 5.9 years and unmarried men took on average 6.4 years. Also as in science, female historians are far more likely to have a partner also in academia than men.

Recorded Venture Capitalist' Conversations Show How Differently They Talk About Female Entrepreneurs (Malmstrom et al. 2017)

"Men were characterized as having entrepreneurial potential, while the entrepreneurial potential for women was diminished. Many of the young men and women were described as being young, though youth for men was viewed as promising, while young women were considered inexperienced. Men were praised for being viewed as aggressive or arrogant, while women’s experience and excitement were tempered by discussions of their emotional shortcomings."

"Unsurprisingly, these stereotypes seem to have played a role in who got funding and who didn’t. Women entrepreneurs were only awarded, on average, 25% of the applied-for amount, whereas men received, on average, 52% of what they asked for. Women were also denied financing to a greater extent than men, with close to 53% of women having their applications dismissed, compared with 38% of men. This is remarkable, given that government VCs are required to take into account national and European equality criteria and multiple gender requirements in their financial decision making."

Citation: (2017) Gender Stereotypes and Venture Support Decisions: How Governmental Venture Capitalists Socially Construct Entrepreneurs’ Potential. DOI: 10.1111/etap.12275Minorities who whiten resumes get more interviews (Kang, S. et al., 2016)

"Twenty-five percent of black candidates received callbacks from their whitened resumes, while only 10 percent got calls when they left ethnic details intact. Among Asians, 21 percent got calls if they used whitened resumes, whereas only 11.5 percent heard back if they sent resumes with racial references."

Kang, S. et al. (2016) Whitened Résumés: Race and Self-Presentation in the Labor Market.